Shifting Geographies

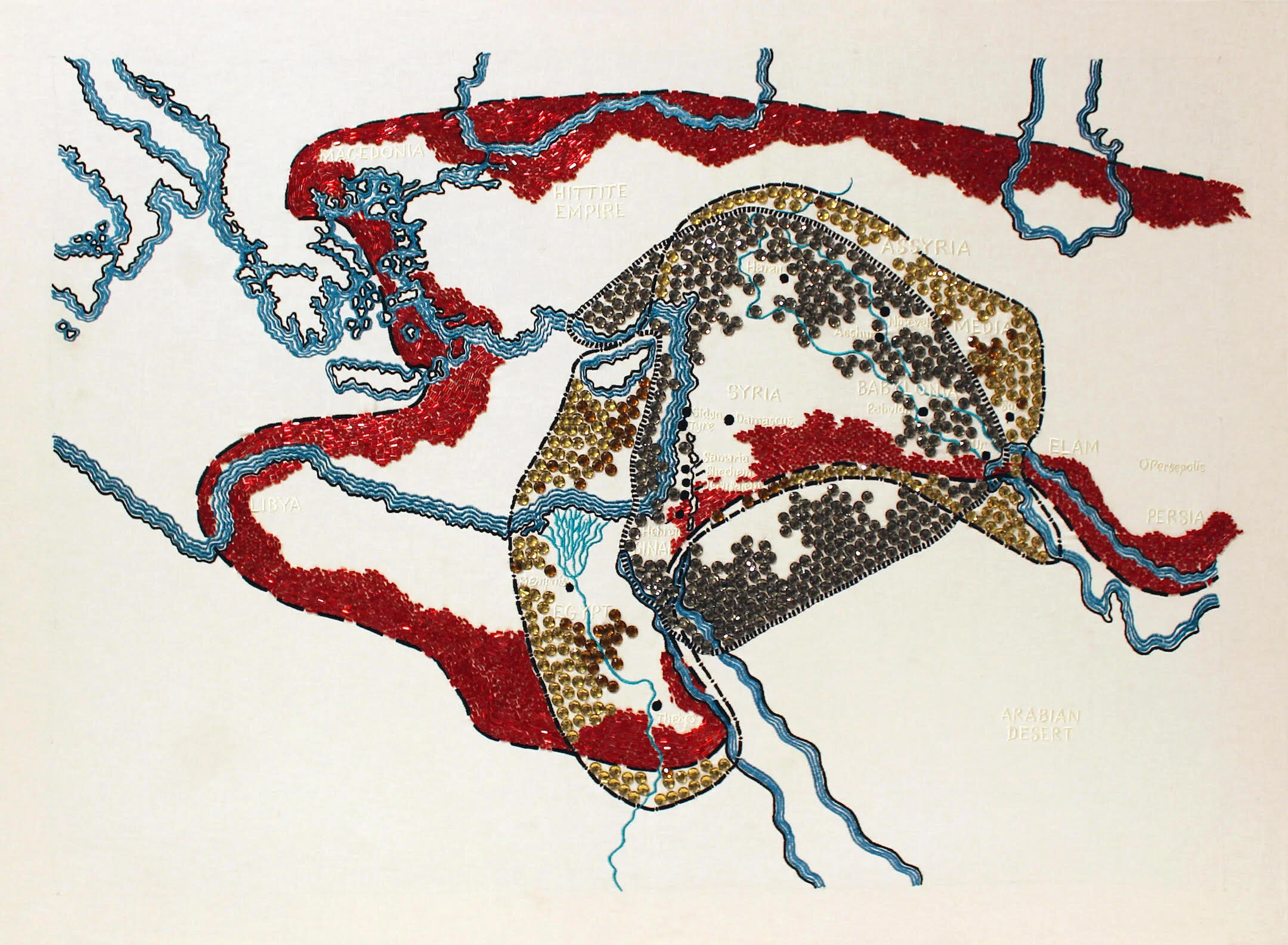

Chung’s maps either depict specific moments or diachronic layers of history, narrated through the visible effects of spatial transformation. Sourcing archival documents, topographic maps, cartogram charts, projected urban plans, infographics, and oral histories. Chung plays with such representations of space as captures of temporality, as reflections of utopian and dystopian visions, as documents of power exploitation and forced displacement. By pushing and pulling, combining and isolating, punctuating and collecting elements of these isolated strata, they invoke the palimpsestic nature of cityscapes and nationscapes as they have undergone urban renewal or territorial restructuring. They are abstractions of abstractions, playing upon James C. Scott’s descriptions of maps as instruments designed to summarize, abstract, and render legible geographical and human landscapes.[1]

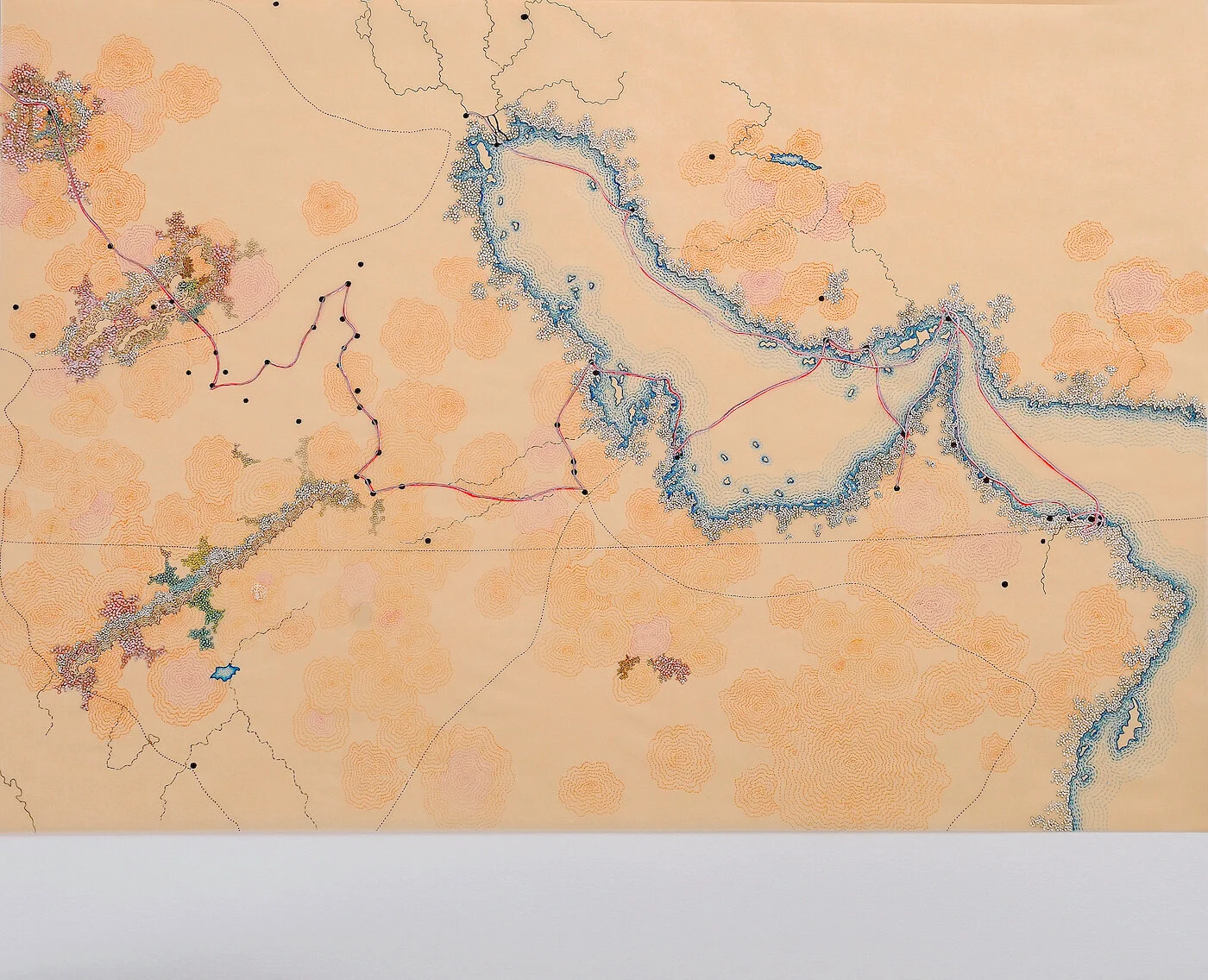

Life, which you look for, you will never find–the ancient Near East | 2015 | embroidery, beads, plastic gems | 85 x 115 cm

Straight Line carved and shaped the region: the secret deal of the 1916 Sykes & Picot Agreement | 2014 | 110 x 70 cm

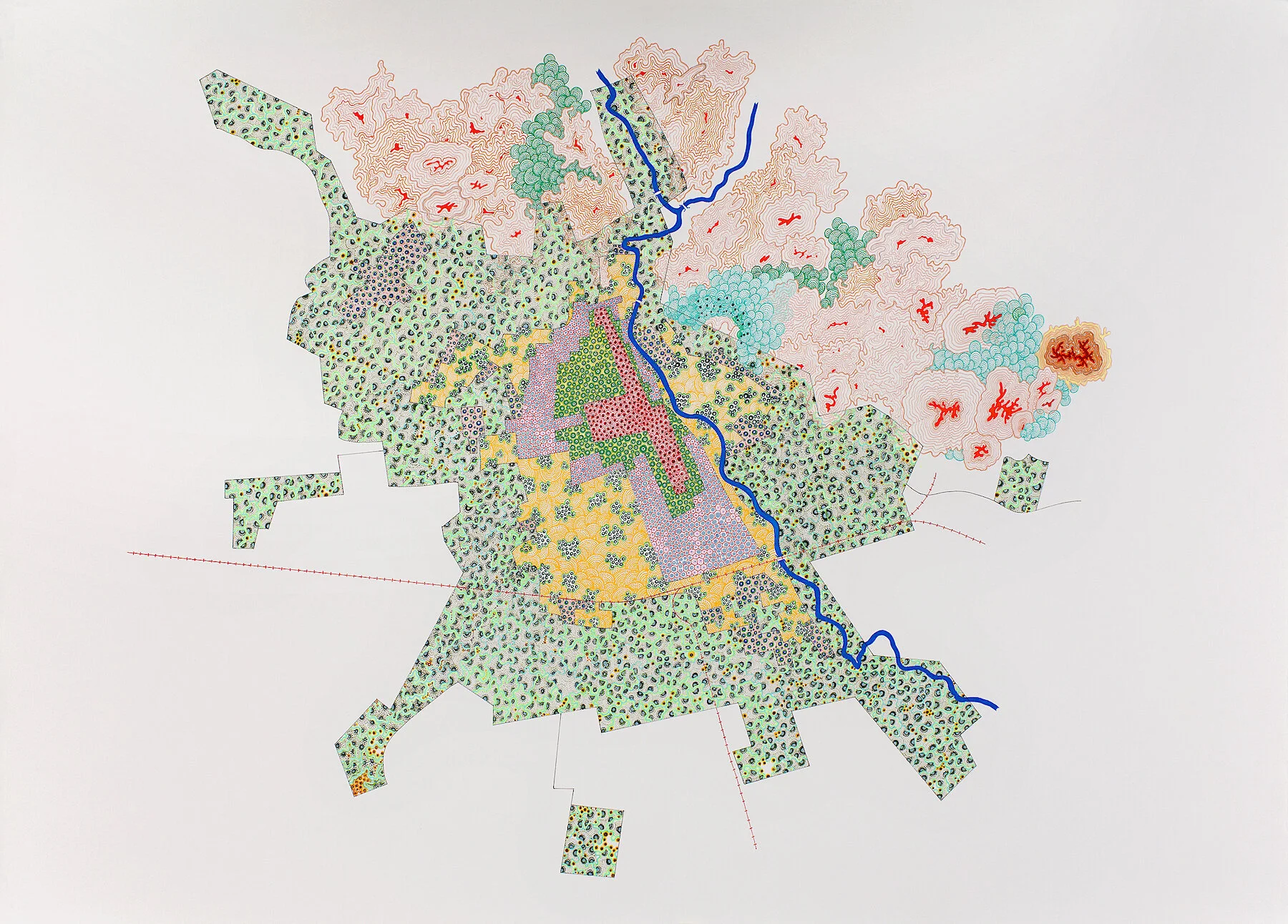

Recovering Beirut: half-way between the imaginary and reality, 1964-2016 | 2012 | 80 x 100 cm

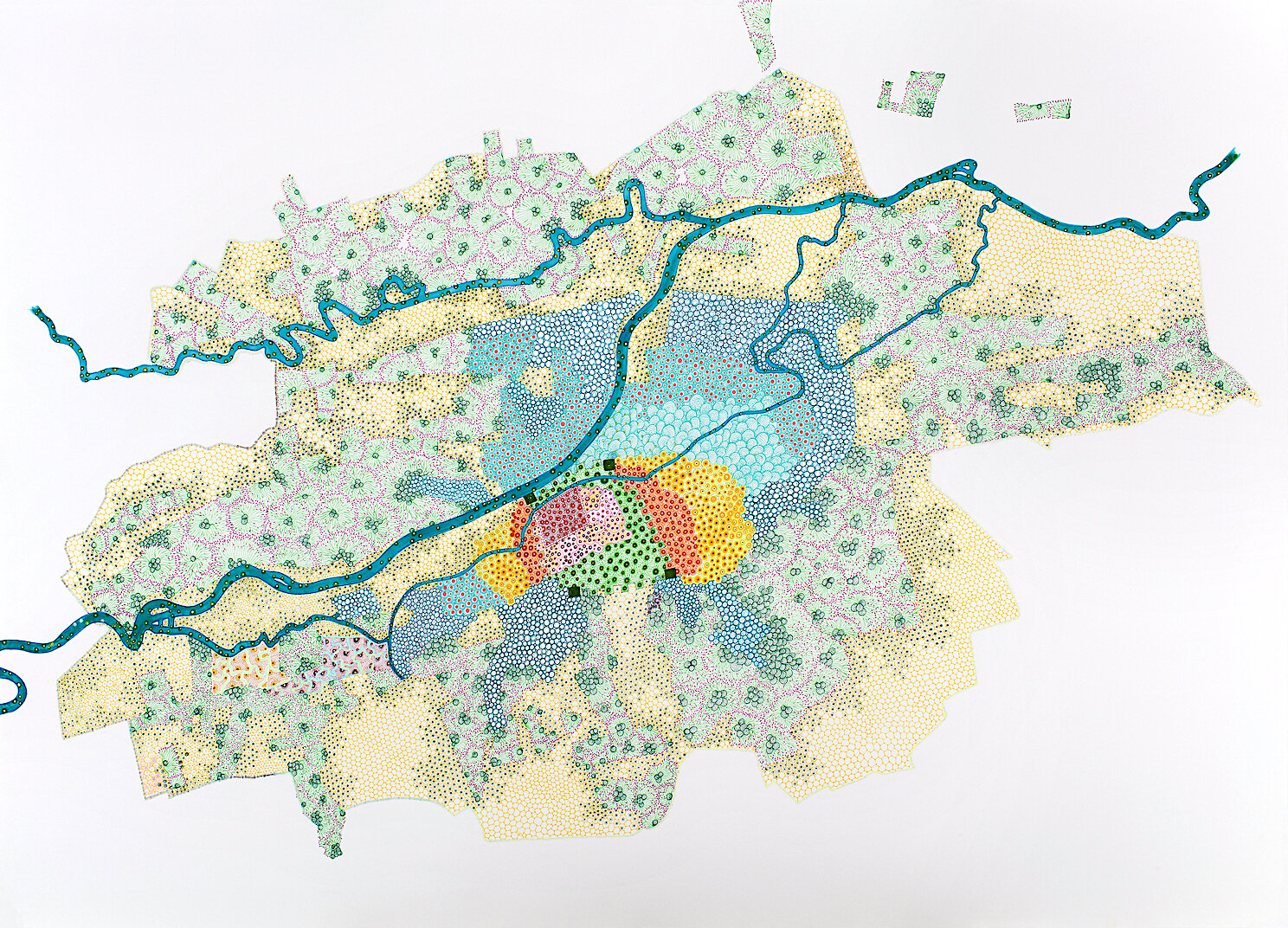

The Growth of Cali - city boundaries: 1780, 1880, 1921, 1930, 1937, 1951 | 2012 | 98 x 135 cm

Development Stages of Cluj from 12th Century to 1957 | 2012 | ink and oil on paper | 98 x 135 cm

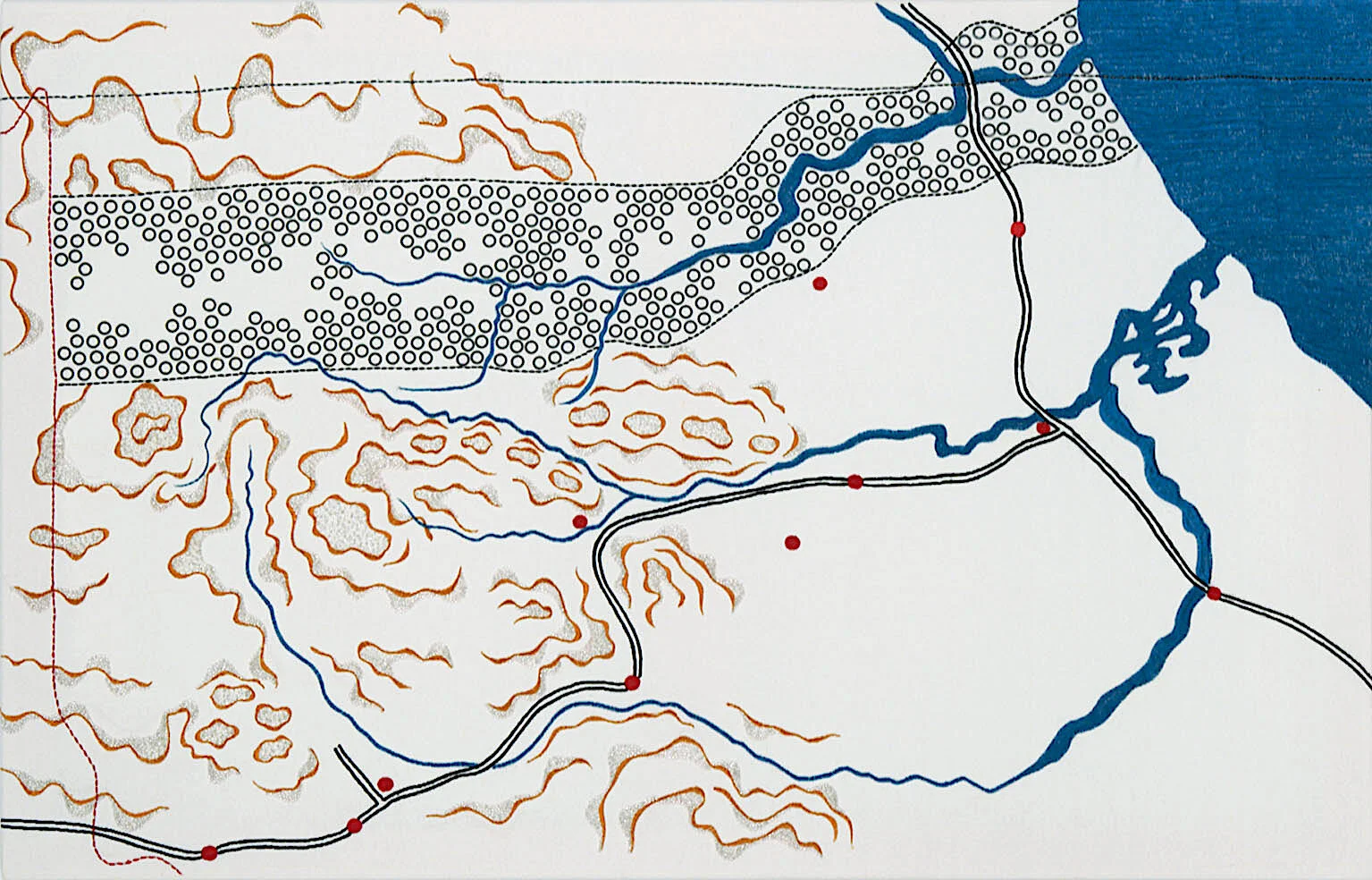

Iraqi State Railways after Anglo-Iraqi Treaty 1930 & current pipelines | 2010 | 100 x 63cm

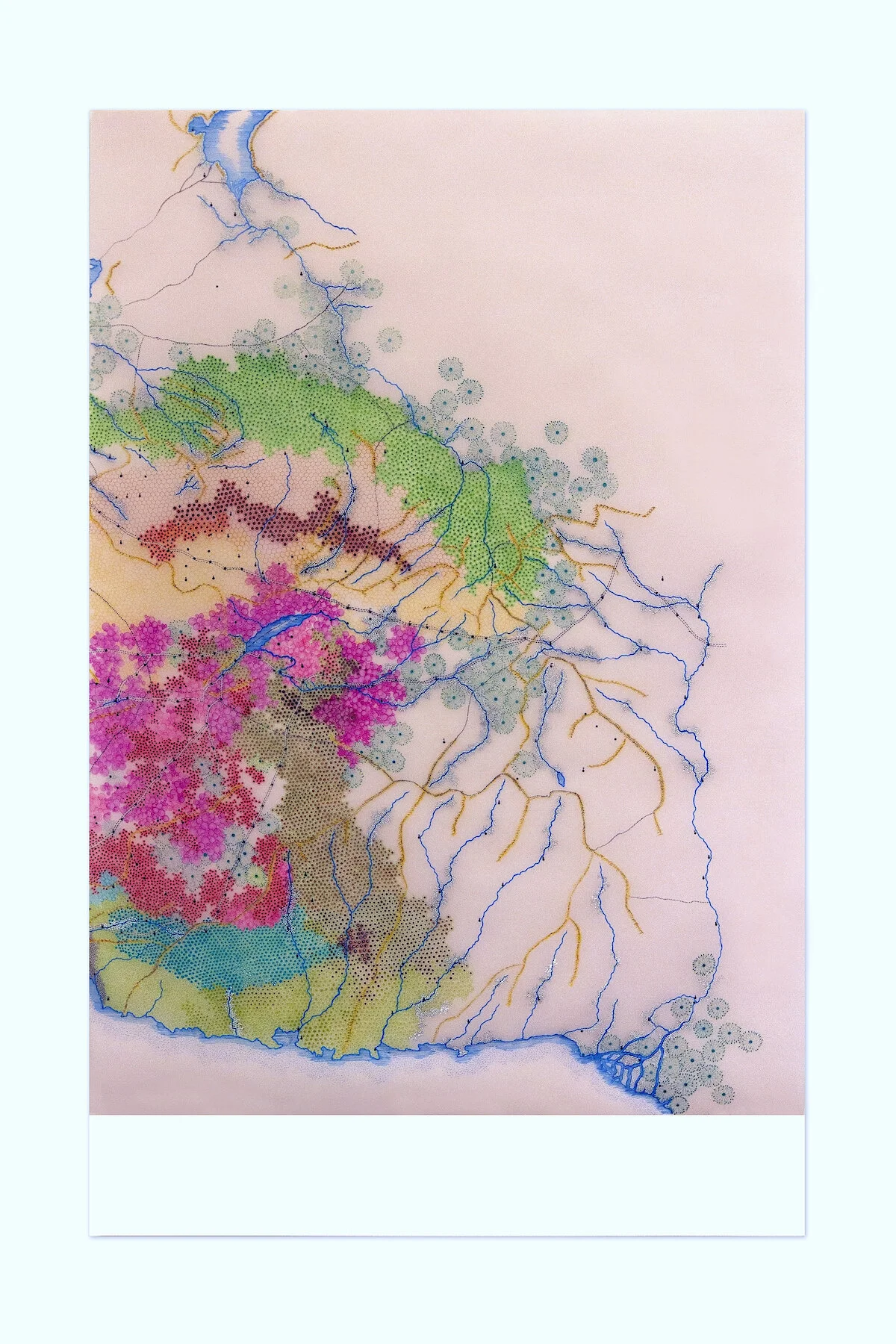

The Gulf in a map of the Persian Empire by Mons. D’Anville | 2014 | ink & oil on vellum and paper | 110 x 70 cm

The Arabian Sea in a map of the Persian Empire by Mons. D’Anville | 2014 | 110 x 70 cm

The Routes of W.G. Palgrave through the Gulf 1862-1863 | 2013 | 71 x 88 cm

The Heart of Sharjah Project 2025 | 2013 | 75 x 91.5 cm

25º15'8"N 55º16'48"E Dubai 1973 | 2010 | 110 x 165.5 cm

25º15'8"N 55º16'48"E Dubai 2020 | 2010 | ink, oil and Copic marker on Arches paper | 110 x 165.5 cm

top: Frontier of Tibet as claimed by Tibetans in 1914; bottom: Frontier of Tibet as claimed by Nationalist Chinese in 1914 | 2010 | 100 x 63 cm

top: Frontier of Tibet proposed at the 1914 Tripartie Simla Conference; bottom: Territories under control of Dalai Lama’s Gov (1918-1950)

Kaesong Armistice Conference Site 1951 | 2010 | embroidery, beads, metal grommets, buttons on canvas | 112 x 86cm

DMZ-17th Parallel | 2010 | embroidery, beads, metal grommets on canvas | 70 x 109cm

Berlin Wall | 2010 | embroidery, metal grommets, buttons on canvas | 84 x 112cm

Cold War Europe | 2010 | embroidery, beads, metal grommets, buttons on canvas | 85 x 110cm

Tangier 1943: the international zone | 2012 | ink and oil on paper | 110 x 180 cm

In Chung’s cartographic work, the layering or juxtaposing of maps from different eras in history of a country or city reflects the impossibility of accurately creating a cartographic representation of a place, as the geographic boundaries of many countries and cities are continuously being changed, shifted, and erased. The map Recovering Beirut: half-way between the imaginary and reality, 1964-2016 exemplifies this impossibility, as its boundaries are continually redefined by wars and religious conflicts. The Growth of Cali—city boundaries: 1780, 1880, 1921, 1930, 1937, 1951, 2012 and Development Stages of Cluj from 12th Century to 1957 map these cities’ growth patterns and shifting borders over time.

The layering or juxtaposing of maps also reveals the connection between past imperial violence and contemporary economic & political motivations. The map Iraqi State Railways after Anglo-Iraqi Treaty 1930 combines an original map of Iraq State Railways in 1930 with a 2007 map that shows the main oil pipelines, comparing the 1930 Anglo-Iraqi treaty with the 2007 US-Iraqi agreement. Oil deals and transportation routes as political trade-offs appear like architectural blueprints with landscape design. The diptych, the Gulf & Arabian Sea in a map of the Persian Empire by Mons. D’Anville, overlays a map of the Persian Empire with charts showing the major geological subdivisions of Iran modified after Stöcklin 1968, 1977, Nabavi 1976, and publications of the Geological Survey of Iran (Nezafati 2006). These maps allude to the use of geologic mapping in assisting the assessment of oil and gas resources.

Another two maps depicting the Persian Gulf, The Routes of W.G. Palgrave through the Gulf 1862–1863 and The Heart of Sharjah Project 2025, reflect the continuity of imperialist ideology and ambitions in current visions of modernity. The first one is drawn based on the account of the British traveler/scholar William Gifford Palgrave, who traveled through the Gulf with a mission of gaining better knowledge of Arabia to benefit French imperialistic schemes in Africa and the Middle East. The latter is based on the ‘Heart of Sharjah’ plan, an ambitious historical preservation and restoration project of the heritage district to be finished in 2025. Chung traveled to the city of Sharjah and recognized the street patterns she had rendered in her map. As she walked through the city and observed those living in areas outside of the heritage quarters, Chung asked herself for whom the ‘Heart of Sharjah’ project was being carried out.

The political motivations behind the use of cartographic tools are consistently exemplified in Chung’s maps – their complex involvement in politicizing ideas of border control, zones of neutrality and the formation of national coalitions as political maneuvers, as in the four maps of Tibet, Berlin Wall, Cold War Europe, Kaesong Conference Site 1951 [on North and South Korea], DMZ – 17th Parallel, and Tangier 1943. When examining a map of a certain locality through the lens of its history and cultural memories at a particular time period, one can unveil realities and perspectives that were hidden behind the map’s mechanical representation of that place. The map Tangier 1943: the international zone refers not only to the city’s historical status as a place of international convergence, but also to a site that western powers frantically exercised their ambitions and political moves against one another as the dusk of World War II was approaching. The year 1943 significantly reflects the political and cultural conditions of the early 1940s in Tangier and Morocco, when the first efforts toward the first efforts toward Moroccan independence were developing – with the French capitulation in World War II, the forming of Moroccan Communist Party and the National Party becoming Istiqlal Party in 1943, and the call for the independence of Morocco in 1944.

[1] James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998), 87.

Related Exhibitions:

New Cartographies | Asia Society Texas Center, Houston | 2018-2019

Demarcate: Territorial Shift in Personal and Societal Mapping | San Jose ICA, CA | 2016

Migration Politics: Three CAMP exhibitions at the SMK | Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen | 2016

All The World's Futures | 56th Venice Biennale | 2015

Disrupted Choreographies | Carré d’Art-Musée d’art contemporain de Nîmes, France | 2014

Re:emerge: Towards a New Cultural Cartography | Sharjah Biennial | 2013

California-Pacific Triennial | OCMA, Newport Beach | 2013

Six Lines of Flight | San Francisco MoMA | 2012

The Map as Art | Kemper Art Museum, St. Louis, MO | 2012

Scratching the Walls of Memory | Tyler Rollins Fine Art, New York | 2010